Alright, folks, let’s talk about PEEP and inspiratory time (I-time). These two ventilator settings can be powerful tools in our arsenal for improving oxygenation, but they can also be a double-edged sword if used incorrectly. Think of it like giving a potent medication – the right dose can be life-saving, but the wrong dose can be disastrous. So, let’s dive into the physiology, the “why” behind these settings, and how we can use them safely and effectively.

The Pathology: Why We Need Mean Airway Pressure (MAP)

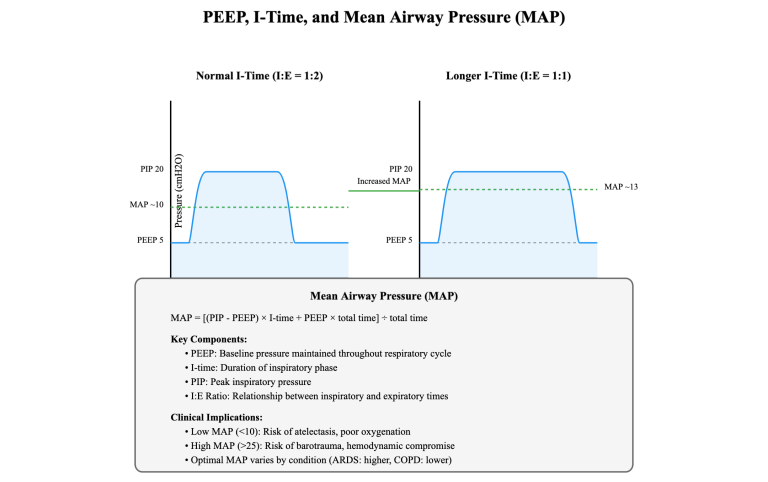

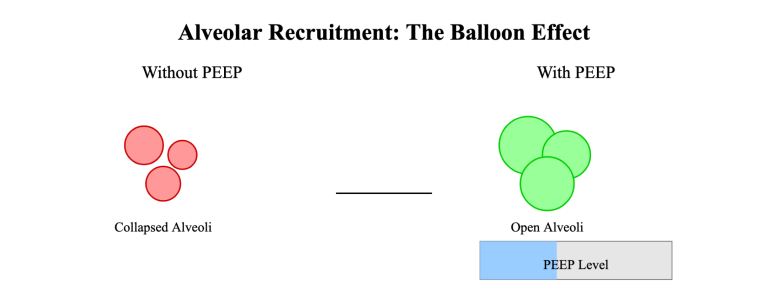

Before we jump into the settings, let’s quickly review why manipulating mean airway pressure (MAP) is so important. MAP is the average pressure in the airways during a complete respiratory cycle. It’s a crucial determinant of alveolar recruitment (opening collapsed alveoli) and, consequently, oxygenation. Think of your lungs like a bunch of tiny balloons. In conditions like ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome), these balloons collapse, making gas exchange difficult. Increasing MAP helps to pop those balloons back open, increasing the surface area for oxygen to diffuse into the bloodstream.

PEEP: The Balloon Inflator

PEEP, or Positive End-Expiratory Pressure, is the pressure maintained in the airways at the end of exhalation. It’s like keeping a little bit of air in the balloons to prevent them from completely collapsing. This “splinting” open of the airways improves gas exchange and reduces atelectasis (alveolar collapse).

I-Time: The Time to Fill the Balloons

I-time, or inspiratory time, is the duration of the inspiratory phase of each breath. It’s the time allotted for the ventilator to deliver the tidal volume. A longer I-time allows for more complete alveolar filling and can contribute to a higher MAP. Think of it as how long you have to inflate each balloon. The longer you blow, the bigger it gets (up to a point, of course!).

The Balancing Act: PEEP and I-Time Synergy

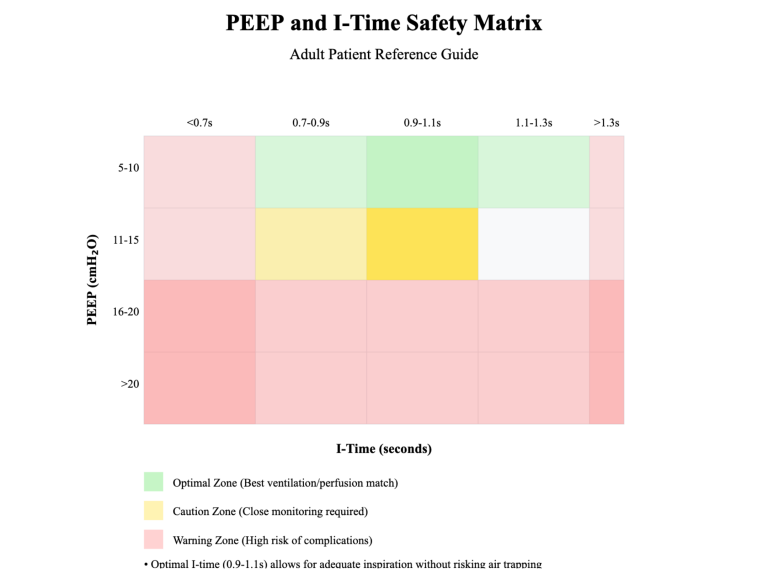

Now, here’s where the magic (and the potential for mayhem) happens. PEEP and I-time work together to influence MAP. Increasing either one can increase MAP, but the combination is key. We want to find the sweet spot where we maximize alveolar recruitment and oxygenation without causing lung damage.

The Danger Zone: Overdistension and Barotrauma

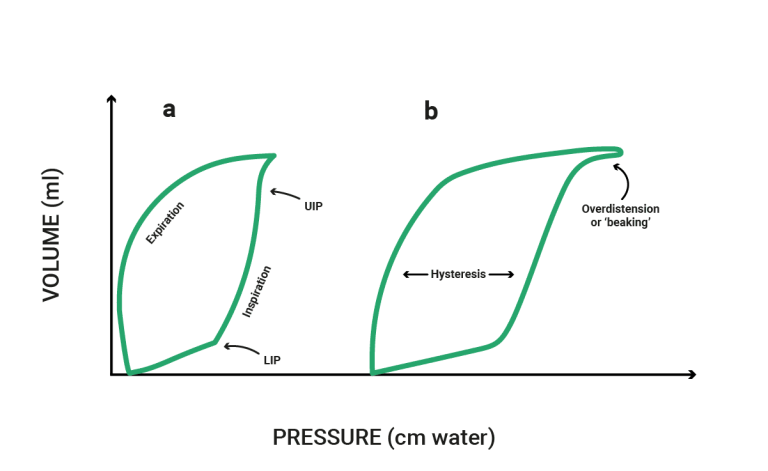

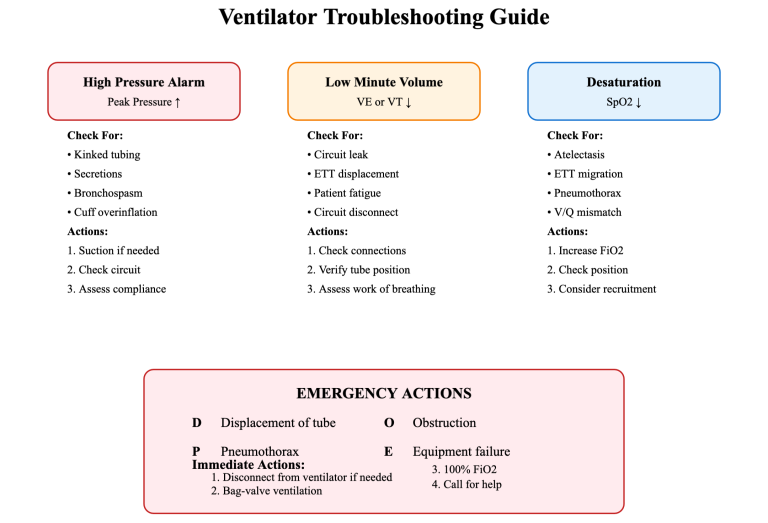

Remember those balloons? If you overinflate them, they’ll pop. The same principle applies to the lungs. Excessive PEEP or I-time can lead to overdistension of the alveoli, resulting in barotrauma (lung injury due to pressure). This can manifest as pneumothorax (air leaking outside the lung) or other nasty complications. This is why we need to be cautious and judicious with these settings.

PEEP Above 10 mmHg: Proceed with Caution!

The general rule of thumb is to be very careful when increasing PEEP above 10 mmHg. While there are definitely situations where higher PEEP is necessary (e.g., severe ARDS), it should always be done in conjunction with optimizing other ventilator settings, particularly I-time, and with close monitoring of the patient. Just cranking up the PEEP without considering I-time is like flooring the accelerator without checking the steering – you’re likely headed for trouble.

Optimizing I-Time: The Secret Weapon?

Often, before significantly increasing PEEP, we should focus on optimizing I-time. A longer I-time can improve gas exchange and increase MAP without necessarily requiring high PEEP levels. This can be particularly beneficial in patients with restrictive lung disease or those with poor lung compliance.

Is It Safe to Increase I-time? Checking the Green Lights:

Before you even think about tweaking that I-time knob, make sure you’ve got the green light:

Patient Stability: Is the patient relatively stable? Are their vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation) reasonably within acceptable limits? A crashing patient isn’t the ideal candidate for I-time experimentation. Address the immediate crisis first.

Ventilator Mode: Are you in a volume-control or pressure-control mode? While you can adjust I-time in both, the implications are slightly different. In volume control, changing I-time will directly affect the flow rate. In pressure control, it affects the delivered tidal volume. Understanding your mode is crucial.

Baseline Settings: Know your starting point. What’s your current I-time, tidal volume, respiratory rate, and PEEP? You need a baseline to compare against as you make adjustments.

No Contraindications: Are there any specific contraindications to extending I-time? For example, patients with certain cardiac conditions or those at high risk for dynamic hyperinflation (air trapping) might not tolerate a prolonged inspiratory phase.

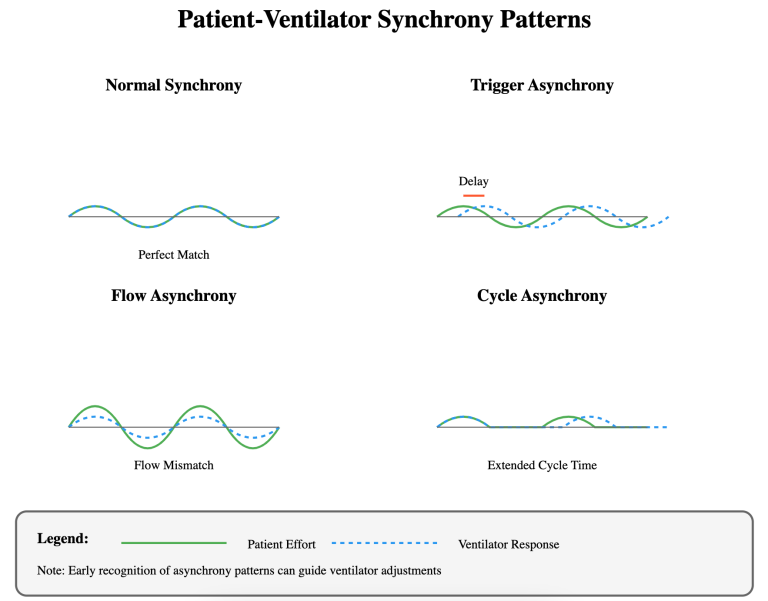

Waveform Wisdom: Clues from the Ventilator

Your ventilator waveforms can give you valuable clues about whether it’s safe to increase I-time:

Flow Waveform: In volume control, a decelerating flow pattern (sloping downwards) during inspiration might suggest that I-time is too short and you’re not achieving full alveolar recruitment.

Pressure Waveform: In pressure control, a “beaking” appearance (a sharp upward deflection at the end of inspiration) can indicate that the set pressure is being reached before the lungs are fully inflated, suggesting a need for longer I-time.

The Pathophysiology of I-time and Why it Matters

Think of the lungs as a complex network of branching airways ending in tiny air sacs called alveoli. Effective gas exchange (oxygen in, carbon dioxide out) requires these alveoli to be open and participating in ventilation. Several pathological processes can disrupt this delicate balance, and I-time plays a crucial role in addressing them:

Atelectasis (Alveolar Collapse): In conditions like ARDS, surfactant deficiency, or post-operative atelectasis, the alveoli collapse, reducing the surface area for gas exchange. Simply increasing PEEP might not be enough if the alveoli aren’t given enough time to inflate. A longer I-time allows for more complete alveolar recruitment, giving PEEP a better chance to do its job.

Reduced Lung Compliance (Stiff Lungs): Diseases like ARDS or pulmonary fibrosis make the lungs stiff and difficult to inflate. These “stiff” lungs require more pressure to open the alveoli. A longer I-time allows for a more gradual and sustained pressure delivery, which can be more effective in recruiting alveoli in these stiff lungs compared to a quick, high-pressure burst.

Ventilator Asynchrony: If the ventilator’s inspiratory phase doesn’t match the patient’s own inspiratory effort, it can lead to inefficient ventilation and discomfort. Adjusting I-time can sometimes improve synchrony, making ventilation more comfortable and effective.

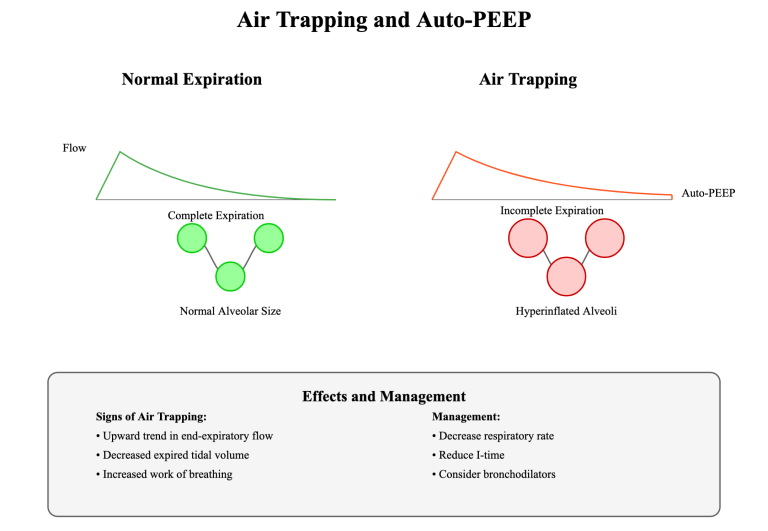

4. Air Trapping/Dynamic Hyperinflation: In conditions like COPD or asthma, patients may have difficulty exhaling completely, leading to air trapping and increased residual volume. While it might seem counterintuitive, sometimes carefully adjusting I-time in conjunction with other settings can improve expiratory time and reduce air trapping. This requires careful monitoring and often involves a multidisciplinary approach. We are not saying to increase the I-time in these patients. We are saying that manipulating the I-time could help with other settings, and it all revolves around the pathophysiology. For example, decreasing the I-time may allow for a longer expiratory time (E-time). This longer E-time may help someone with air trapping.

How I-time Helps (Beyond Just MAP):

Improved Gas Exchange: By allowing more time for alveolar recruitment and gas diffusion, a properly set I-time can directly improve oxygenation (increased PaO2) and carbon dioxide removal (decreased PaCO2).

Reduced Work of Breathing: If the ventilator settings are better synchronized with the patient’s respiratory drive, the patient’s work of breathing can be reduced.

Minimized Lung Injury: By optimizing I-time, we can potentially reduce the need for excessively high PEEP levels, thus minimizing the risk of barotrauma and ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).

Setting I-time Appropriately: A Pathophysiology-Driven Approach

Identify the Underlying Pathology: Is it atelectasis, reduced compliance, asynchrony, or a combination? This will guide your I-time strategy.

Assess Lung Mechanics: Look at the pressure-volume loops and other ventilator graphics to understand the patient’s lung mechanics. Are the lungs stiff? Is there evidence of air trapping?

Start with a Reasonable I-time: Don’t just jump to extremes. Begin with a physiologically reasonable I-time and then make adjustments based on the patient’s response.

Observe the Patient’s Response: Monitor oxygenation, work of breathing, and ventilator waveforms. Are you seeing improvements? Are there any signs of adverse effects?

Titrate Carefully: Adjust I-time in small increments, allowing time for the patient to respond. Don’t make rapid changes without careful consideration.

Consider Other Ventilator Settings: I-time doesn’t work in isolation. It needs to be considered in conjunction with other settings like PEEP, tidal volume, and respiratory rate. For example, in a patient with ARDS and low compliance, you might need a combination of higher PEEP and a longer I-time to optimize alveolar recruitment. In a patient with air trapping, you may need a lower PEEP, a shorter I-time, and a lower respiratory rate to allow for more complete exhalation.

Titrating PEEP and I-Time: The Art and Science

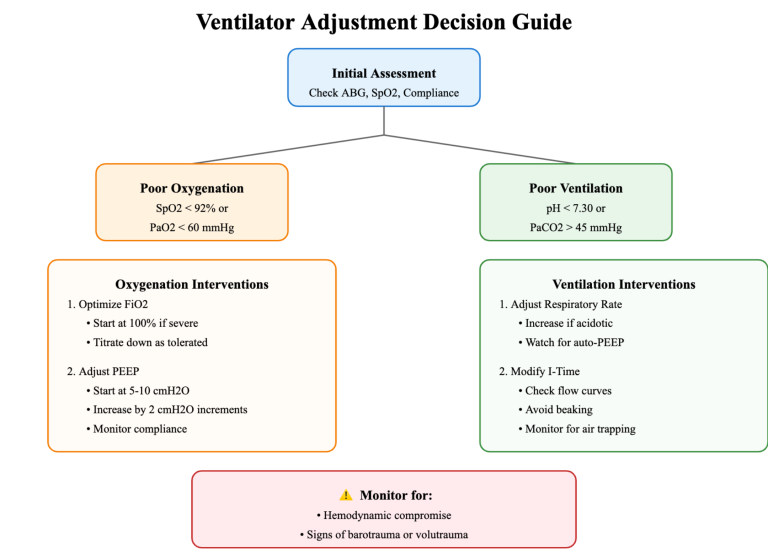

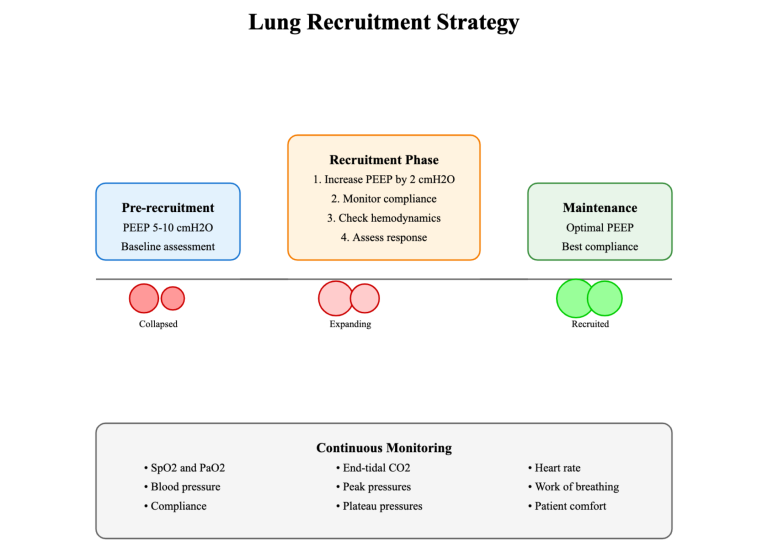

So, how do we find the “sweet spot”? It’s a combination of art and science. We need to consider the patient’s underlying condition, their lung mechanics, and their response to therapy. Here’s a general approach:

- Start Low, Go Slow: Begin with low levels of PEEP (e.g., 5 cmH2O) and a reasonable I-time.

- Assess Oxygenation: Monitor the patient’s oxygen saturation (SpO2), arterial blood gases (ABGs), and chest X-ray.

- Optimize I-Time First: Gradually increase I-time while observing the patient’s response. Look for improvements in oxygenation and lung mechanics.

- Titrate PEEP Carefully: If oxygenation remains suboptimal after optimizing I-time, then consider increasing PEEP in small increments (e.g., 2 cmH2O at a time). Again, closely monitor the patient for any signs of barotrauma (e.g., decreasing lung compliance, increased peak airway pressure).

- Personalize the Approach: Remember, every patient is different. What works for one patient may not work for another. Tailor your approach based on the individual patient’s needs and response.

Case Study 1: ARDS with Refractory Hypoxemia

A 55-year-old male with ARDS secondary to pneumonia is being ventilated in volume control mode with a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, PEEP of 10 cmH2O, and FiO2 of 0.8. His SpO2 remains in the low 80s.

- Intervention: The I-time is gradually increased from 1.0 second to 1.4 seconds.

- Outcome: The SpO2 improves to 92% with a minimal increase in plateau pressure. This suggests improved alveolar recruitment and gas exchange due to the longer I-time.

Case Study 2: COPD Exacerbation with Air Trapping

A 68-year-old female with a history of COPD presents with an acute exacerbation. She is intubated and ventilated in pressure control mode. Initial settings include a PEEP of 8 cmH2O, I-time of 1.2 seconds, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. She exhibits signs of air trapping and dynamic hyperinflation.

- Intervention: The I-time is decreased to 0.8 seconds, and the respiratory rate is reduced to 16 breaths/min.

- Outcome: The air trapping resolves, and her ventilation improves, as evidenced by a decrease in PaCO2 and improved synchrony with the ventilator.

Case Study 3: Post-Operative Atelectasis

A 45-year-old male develops atelectasis after a major abdominal surgery. He is being ventilated in volume control mode. His SpO2 is 89% on an FiO2 of 0.6.

- Intervention: The I-time is increased from 0.9 seconds to 1.3 seconds.

- Outcome: His SpO2 improves to 94%, suggesting that the longer I-time helped to recruit collapsed alveoli.

Case Study 4: Trauma Patient with Lung Contusions

A 30-year-old male sustains bilateral lung contusions in a motor vehicle accident. He requires mechanical ventilation. Initial settings include a PEEP of 5 cmH2O and an I-time of 1.1 seconds. His oxygenation is borderline.

- Intervention: The I-time is cautiously increased to 1.5 seconds, while closely monitoring his plateau pressure.

- Outcome: His oxygenation improves without any signs of barotrauma, likely due to increased alveolar recruitment in the injured lung regions.

Case Study 5: Patient with Pulmonary Fibrosis

A 70-year-old female with pulmonary fibrosis requires mechanical ventilation due to respiratory failure. Her lungs are stiff and difficult to ventilate.

- Intervention: A longer I-time of 1.6 seconds is used in conjunction with a moderate level of PEEP.

- Outcome: This strategy allows for more effective gas exchange in the setting of decreased lung compliance.

Case Study 6: Morbidly Obese Patient

A morbidly obese patient requires mechanical ventilation. Due to their body habitus, they have reduced lung volumes and decreased chest wall compliance.

- Intervention: A longer I-time is used, and careful attention is paid to their tidal volume and plateau pressure to avoid overdistension.

- Outcome: The longer I-time, in conjunction with other appropriate settings, helps to improve their oxygenation and ventilation.

Case Study 7: Neuromuscular Weakness

A patient with Guillain-Barre syndrome experiences respiratory muscle weakness and requires mechanical ventilation.

- Intervention: Adjusting the I-time helps to optimize the delivery of each breath and improve synchrony with the ventilator, as their respiratory drive may be weak or irregular.

- Outcome: Careful titration of I-time contributes to improved ventilation efficiency and patient comfort.

Case Study 8: Pediatric Patient with Bronchiolitis

A young child with severe bronchiolitis requires mechanical ventilation. Due to their small airways, they are prone to air trapping.

- Intervention: A shorter I-time may be necessary to allow for adequate expiratory time and prevent dynamic hyperinflation. Close monitoring is crucial.

- Outcome: Careful I-time management in this population helps to prevent complications associated with air trapping.

Important Note: These are simplified examples for illustrative purposes. Real-world ventilator management is complex, and these cases should not be used as a substitute for clinical judgment and consultation with experienced healthcare professionals.

Individualized Approach, Monitoring, and Collaboration:

- Individualized Approach: Every patient is unique, and their ventilator settings should reflect that. Consider their underlying condition, lung mechanics, and response to therapy when adjusting PEEP and I-time. What works for one patient may not work for another.

- Monitoring and Reassessment: Ventilator management is a dynamic process. Continuously monitor your patient’s vital signs, oxygenation, ventilation, and ventilator waveforms. Reassess their response to any adjustments and be prepared to modify your strategy as needed.

- Communication and Collaboration: Effective communication and collaboration are essential for optimal patient care. Discuss your ventilator strategy with your medical director, respiratory therapist, and other healthcare professionals involved in the patient’s care. Share your observations and concerns, and work together to develop a comprehensive plan.

A Humble Paramedic’s Wisdom (and Humor)

Look, I’m just a humble paramedic/educator, not a fancy doctor. But I’ve learned a few things over the years. One thing I’ve learned is that ventilation is both a science and an art. We need to understand the physiology, but we also need to be observant and adaptable. And remember, when in doubt, consult with your medical director or a respiratory therapist. They’re the real experts!

Call to Action:

- Continuing Education: Never stop learning! Pursue further education and training in mechanical ventilation to stay up-to-date on the latest evidence and best practices.

- Clinical Practice: Apply the concepts discussed in this blog post to your own clinical practice. Be mindful of PEEP and I-time, and how they can be adjusted to optimize your patient’s ventilation and oxygenation.

- Feedback and Discussion: I’d love to hear from you! Share your own experiences and insights in the comments section below. Let’s learn from each other and continue to improve the care we provide to our patients.

References:

- The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. (2000). Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 342(18), 1301-1308.

- Hickling, K. G., Walsh, J., Henderson, S., & Jackson, R. (2008). Low tidal volume ventilation and lung-protective strategies in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care Medicine, 36(1), 1-10.

- MacIntyre, N. R. (2017). Evidence-based guidelines for mechanical ventilation: What is new? Respiratory Care, 62(3), 322-340.

- Peñuelas, O., & Frutos-Vivar, F. (2013). Lung-protective ventilation. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 19(1), 76-83.

- Gattinoni, L., Caironi, P., Cressoni, M., Chiumello, D., Ranieri, V. M., Quintel, M.,… & Marini, J. J. (2017). Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(9), 895-907.

- Guyatt, G. H., Meade, M. O., & Esteban, A. (for the LUNG SAFE Investigators). (2016). Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(23), 2207-2217.

- Bellani, G., Laffey, J. G., Pham, T., Fan, E., Brochard, L., Esteban, A.,… & Slutsky, A. S. (for the LUNG SAFE Investigators). (2016). Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA, 315(8), 788-800.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022). Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/acute-respiratory-distress-syndrome-ards

Disclaimer: This blog post is for educational purposes only. Always follow your local protocols and consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any medical concerns.